Peyto Lake by Frank Kovalchek

Not sure if you can just download and publish that great photo of a gorgeous lake alongside the newest post on your green blog? Read on to find out how to use the wealth of the web’s public domain legally and what to watch out for in my case studies at the end of this post.

Walking Towards Public Domain

Today, there is an incredible excess of information flow in the media and online world. Ideas, art works and texts are being shared with the speed of light (and often without asking), becoming accessible to people around the world more and quicker than ever. The usual barriers of distance are now overcome with almost no difficulty. Everything is just one click away, really. But who protects the rights of the authors in this sharing system? Where is the possibility for them to keep up with it all and manage the sharing of their creations, their very own intellectual property? And which images from those millions you find on the Internet can you use freely without fearing a possible lawsuit?

Copyright was created long before the emergence of the Internet. This legal concept is granting the creator of the original work exclusive rights to it. This can make it hard to do what we today take for granted: copy, paste, edit, and post to the Web. Creative Commons (CC) is a non-profit organization that brings an interesting alternative to full copyrights. Convenient especially for businesses, works marked with the CC licenses can be used also for commercial purposes. You’ve most likely come across this type of licenses on creative networks such as Flickr, Youtube or 500px. For example in October 2011, Flickr alone featured over 200 million Creative Commons licensed photos. That is a pretty nice photo bank from CC Commons for us to be used, and it’s a free one!

Founded by Lawrence Lessig, Hal Abelson, and Eric Eldred in 2001, Creative Commons took it one step further by promoting “sharing of creative works and diffusing ideas to produce cultural vibrance, scientific progress and business innovation.” Supporting the copyleft movement (as opposed to copyright), they try to work towards a richer public domain. The basic concept is to encourage sharing of works, but control it as well by having certain rules about how to give credit to the author. When you apply a CC license to your work, you give permission to anyone to use the work for the full duration of the applicable copyright. You want to be careful here, CC licenses are not revocable!

Types of Creative Commons Licenses

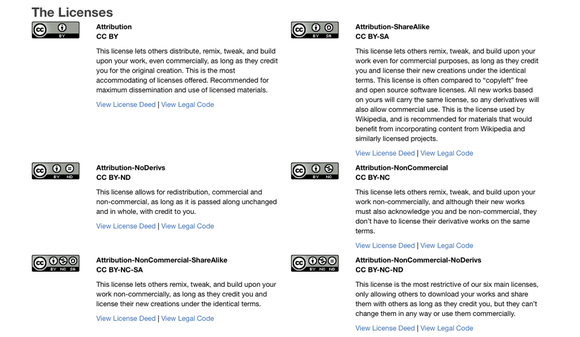

Not to have it too easy after all, you want to pay close attention to the type of the license when planning to use an artwork you find online. The organization released four different CC modules (free of charge to the public) that form six CC licenses. They differ in rights which are reserved for the creator and which are offered to the recipient. There is also one additional license-like contract, the CC0 option, which basically means “No Rights Reserved”. The six available licenses are following:

- Attribution (CC BY) requiring clear attribution to the original author

- Share Alike (CC BY-SA) allowing derivative works under the same or a similar license

- No Derivatives (CC BY-ND) allowing using ONLY the original work, without derivatives

- Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC) the work is not to be used for commercial purposes

- Non-Commercial Share Alike (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Non-Commercial No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND)

A brief overview of the six CC Commons licenses

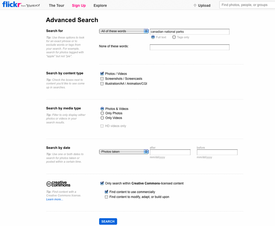

The first three options are the ones that are relevant for you if you’re looking for images to be used for commercial purposes (on your website, blog or in newsletters). Make sure that when browsing the Flickr photo database you use the advanced search. This filter will save you tons of time choosing the right photo only to find that annoying phrase “all rights reserved” beside it. I will talk about this more in the Case Study #1 on how to illustrate an online article.

Case Study #1: How to Search for Photos on Flickr

Flickr Advanced Search Tool

Let’s go through the process of illustrating this post using an image that I “borrowed” using the CC commons license under which it was uploaded to Flickr. In the Advanced Search I typed in the keyword “canadian national parks” and checked the two CC options at the bottom allowing me to freely use the photo commercially on this website (I don’t want to modify it in any way, so I left the last option unchecked). This filter should only show those photos which are enabled for sharing by their authors.

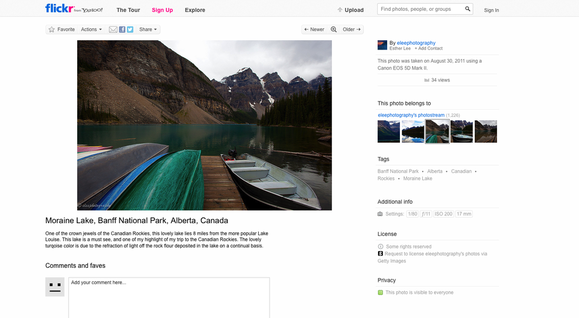

I am using the word “should” because even the first photo of Moraine Lake that I wanted to use wouldn’t work and actually should not be listed in my filtered results in the first place. Why? First of all, it has the author’s watermark with clear symbol of copyright (meaning all rights reserved). This is another flaw in this system that you need to pay extra attention to: in the right bottom corner it says “some rights reserved” but putting the watermark on the photo says a completely different thing. Flickr relies on the user to set up these options and in this particular case, the author either didn’t understand the settings or didn’t bother with them at all. Secondly, you can see the recently introduced symbol of the Getty Images License which means that Getty Images has an agreement with the author to further promote and sell the photo. So it’s not so free to be used after all. Using such a photo could result in receiving a note from Getty Images with a nice bill (see Case Study #2 for more on this). Not many people know about this change and since it is also not recognized by the filter yet, they could get into big trouble for not being informed. Stay away from these photos! Best case scenario, you simply take down the image and replace it with an apology. But you might also end up arguing with Getty Images lawyers or even paying quite a lot of cash!

Case Study #1: This photo from my results has a watermark and Getty Images license

The second photo of Peyto Lake I chose was all right. It’s also a good idea to double check everything by visiting the profile of the photographer to see if they did not write anything specific about how to credit their photos (many people require a short message with the link to where you used their work). If they don’t, a commonly accepted way of doing this is to include the name of the author with the link to their Flickr profile in the caption of the image you used just like the one under the first image of this post.

Case Study #2: Dealing With Getty Images

Letter from Getty Images

A novelty with Flickr which makes your life harder is the activity of Getty Images who seem to request to license all the prettiest photos, which legally overruns the CC licenses. This seems not to be incorporated into the filter yet, so always double check as those photos are not available under the CC anymore. Here is one example of what happened after we used one of the images from Flickr (from a fake account, which we only discovered later) on one of our client’s websites not aware that the very same image was uploaded to a second Flickr profile (a real one, apparently) under a Getty Images license.

The client received a long legal letter requesting to pay for using this one single image with an outrageous sum of $950.00 CAD, apparently for their unauthorized use of Getty Images’ photograph. Getty Images even suggested an online payment. So besides always checking ALL license terms of the photos you use, it’s a good idea to keep track of these images and make a screenshot with the license that was attributed to the photo at the time you found it. This will cover you at least partially, should some trouble arise in the future (because it takes a user only a few seconds to change the license of a photo on Flickr). Maybe Flickr should think about preventing users from changing their CC licenses after they’ve decided they want to share their image for free once.

The General Criticism

Getty Images Settlement Demand

One of the main arguments against the loose licenses on creative artwork is that creativity of individuals is too precious of a resource to be exploited by whomever, especially for commercial gain from which the creator does not profit at all. On the other hand, people who are not professionals get more recognition and get their works published. In the latter, it’s a win-win situation.

Another problem is that Creative Commons has issued multiple licenses that are not always compatible when you combine them which can be very confusing. Creative Commons did also one really smart thing; they’re just the service provider, they do not take part in any legal agreement. There is no such thing as a central database of all the CC licensed works so all the responsibility lies on the authors themselves. In other words, if you are experiencing any trouble with abusive users or have any issues with defending your rights, this is your own problem.

Alec Kinnear

Alec has been helping businesses succeed online since 2000. Alec is an SEM expert with a background in advertising, as a former Head of Television for Grey Moscow and Senior Television Producer for Bates, Saatchi and Saatchi Russia.

Thanks for posting this. It answered exactly what I was wondering about Flickr and Getty Images. I wish their wording were not so confusing.